Friday, May 9, 2008

Thursday, April 24, 2008

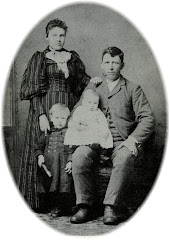

Family History [by Jesse T. Rees- 1956]

On a hot, summer day in the year 1888, John was driving his father's sheep home from the summer range when he stopped at a farm to give his horse rest and water. Here he met and fell in love with Mary Hammer. After a short courtship, they decided to marry although both were quite young-- John, 18, Mary, 17. Mary was born in Smithfield on November 25, 1871.

In Logan of that year they were married in the Logan Temple. Following the ceremony a wedding supper and reception was held at Mary's home in Smithfield.

John and Mary lived in Smithfield for a few years, then moved to Benson where John helped his father with the farm. They built a home in Benson and spent the remainder of their lives there.

John was a good farmer and was happy and contented with his work. As more machinery came into use, he became adept at operating and repairing them. He owned one of the first grain binders in that area and for many years cut grain all over the valley. He also hauled milk from the farms to the factory. He was elected constable by his neighbors and fellow farmers, showing they respected his honesty and good judgment. He worked hard and except for Sundays took time off on rare occasions however, he never failed to attend the County Fair for three days nor to celebrate the 24th of July [the day the Mormons entered Salt Lake Valley].

Although he did not particularly seek out public or religious office, he encouraged his wife, Mary, to take part in community and church affairs. He was a cheerful baby-sitter while she worked in the ward as organist, Relief Society teacher, President of the YWMIA, etc. He was always very proud of her accomplishments.

John died on May 12, 1920; Mary died February 19, 1949. They are buried in the Hyde Park Cemetery.

John and Mary had the following children: Guy Leslie, Ronald, Clifford, Thresa May, John Lawrence, Elston Marion, Simpson Molen, Mary Viola, Teague Thain and Ruthvan LeRoy.

Haun's Mill Tragedy

Historical Note: Mary Nancy Elizabeth Hammer’s grandfather, Austin Hammer was murdered at Haun’s Mill, Missouri on the 30th of October 1838. Her father, John Austin Hammer recorded his memories of that day:

“Austin Hammer (my father) was the son of John Hammer and Nancy York Hammer. He was born in the state of South Carolina, May 6, 1804, and obeyed the gospel in 1835 in Henry County, state of Indiana. He moved to Clay County, Missouri, where he stayed a short time and soon after settled in Caldwell County, and made a cash entry of 120 acres of land and raised one crop of corn. His farm was within three or four miles of Haun's Mill, both situated on Shoal Creek.

In the fall of 1838, the mob threatened to burn this mill because it ground grain for the Mormons, and all the mills in that section of the country, controlled or owned by the mob party, refused to grind for them, hoping by so doing to starve the Mormons out. In consequence of these threats, a few of the brethren assisted in guarding the mill. This duty they had performed for several days and nights. The mob kept repeating their threats of violence. Finally some of our leading men interviewed the mob leaders who agreed upon a certain day when they would send a committee to the mill to confer with our brethren and see if terms could be agreed upon whereby a compromise could be arranged. On the day thus fixed, being the 30th of October, a number of our brethren were at the mill hoping to have something of a reasonable talk, being of course, anxious that peace and security might be restored. With this understanding entered into, no violence from the mob party on that day was anticipated, and the brethren stacked their arms. The mob committee, however, did not make their appearance, but as the day was drawing to a close, a company of the mob, some two or three hundred strong, were seen partly sheltered from observation by the heavy timber nearby. Our brethren immediately hoisted a white flag. When the mob saw the flag, they knew they were discovered.

They rode rapidly on, led by Boregard and Comstock, and on their arrival at the mill one of them without saying a word to our men gave orders for their men to fire, which order was obeyed. Their leader then said to the brethren: "All who desire to save their lives and make peace run into the blacksmith shop," whereupon my father and my uncle John York, together with others, ran into the shop, which was immediately surrounded by the infuriated assailants, who commenced firing between the logs, as there was no chinking between them. They also fired through a long opening made at one side of the shop by one of the logs having been sawed out to admit light; and at the same time, they fired through the door which was standing open. Several were killed in the shop, my father being one of the number, seven balls being shot into his body, breaking both thigh bones. Some of the brethren thus shot down were dragged out into the yard so that their murderers might have a better chance and more room to strip them of their clothing. All who had on good coats and boots were rifled of these articles. My father had on a new pair of boots that fitted him tightly and in the efforts to get them off he was dragged and pulled out of the shop and about the yard in a barbarous manner. In his mangled condition, this cruel treatment must have caused him the most excruciating pain.

The brethren, seeing that the mob party were so numerous and bloodthirsty, concluded that it was useless to make any defense. Their only safety was in everyone making their escape the best way they could, which they did by fleeing into the woods and brush, or wherever they could secrete themselves. When the mob had murdered all they could find and robbed a number of their clothing, they retreated.

After the darkness of night had come on, the brethren who were in hiding began to make search for those who had been killed and wounded. My father was found and carried into Haun's house, where he died about 12 o'clock that night. During that night they kept up the search as well as the darkness would permit, but were only able to find the wounded by their groans. All they were able in this manner to find were taken into Mr. Haun's house as soon as possible so as to be protected from being torn or mangled by the hogs with which the woods at that place were full. When daylight had fully come, the brethren who had been spared had to move with great caution, knowing that the mob was liable to fall upon them at any moment, for the purpose of finishing their bloody and damnable work.

Of course, there was no opportunity for affording the dead a decent and respectable burial. There was an old dry well nearby, and the only thing possible to be done was to place all the bodies of the dead into it. They were all put into this well together and the only burial clothes with which they could be clothed were just what this rapacious band of murderous vampires had left upon them. In this manner, seventeen bodies of our brethren found there their place of rest, my father and my uncle York being among the number. At the time of this sad occurrence, I was in the ninth year of my age. I wish here to record a circumstance which occurred exactly at the time this bloody deed was being enacted. I stood in the yard with my mother, my Aunt York, my cousin Isaiah York and some of the smaller children of our two families. Our anxiety, of course, was great as to the fate of the brethren at Haun's Mill, knowing also that my father and uncle had gone there to aid in its protection and assist those of our friends who lived there. We were standing there exactly at the time this bloody butchery was committed and of course, we were all looking eagerly in the direction of the mill. While in this attitude, a crimson colored vapor, like a mist or thin cloud, ascended up from the precise place where we knew the mill to be located and was carried or streamed upward into the sky, apparently as high as our sight could extend. This singular phenomenon like a transparent pillar of blood-remained there for a long time how long I am not now able correctly to state; but it was to be seen by us far into that fatal night, and according to my best recollection now, my mother's testimony was that it was to be seen there until morning. At that hour we had not heard a word of what had taken place at the mill; but as quick as my mother and aunt saw this red, blood-like token, they commenced to wring their hands and moan, declaring they knew that their husbands had been murdered.Our uneasiness through that night was too great to be described, and when daylight came, my cousin rode to the mill in order to learn the facts in relation to what had taken place. On his arrival there, he learned concerning the massacre and brought us word back as soon as possible. The following morning my cousin and myself went to the mill and found that the dead had all been buried in the well by our brethren as before mentioned. We found the hat of my uncle York with a bullet hole made through it on the two sides at or near the place usually occupied by the band, showing that my uncle must have been shot through the head. We, at this time, went into the blacksmith shop previously spoken of, and there saw a sight truly appalling. The earth constituted the floor and in places where there were small hollows in the soil, the blood stood in pools from two to three inches deep. A boy had tried to hide by creeping under the bellows, but was discovered by the ruffians and killed. The boy begged piteously for his life, exclaiming, beseechingly, "Oh! don't kill me, I am an American boy!" But this touching appeal to their patriotism was unheeded, and the innocent and noble boy while thus appealing to the memory of his native country had his brains dashed out which were plain to be seen upon the logs at the time of my visit.

As before stated, during the time of this bloody onslaught the brethren and sisters tried to save their lives by secreting themselves. One young lady by the name of Mary Stedwell secreted herself behind a large log. While in the act of hurriedly throwing herself behind this log, one of her hands received one of the enemy's bullets which passed through it at the palm.

The death of my father left our family in a very helpless and unprotected condition. It would have been an event sufficiently melancholy had he died of sickness, at home, where his family could have administered to his wants, and his last moments been soothed by those attentions which the hand of kindness and affection alone can satisfactorily administer. But to be cut down in his prime and torn thus suddenly and ruthlessly from wife and children so intensified the gloom which rested down upon our bereaved circle, that for a time it seemed that no ray of hope or joy would ever by able to penetrate our bosoms. And could we have been left, uninterrupted, to pass our season of grief that would have been a boon which we had not the privilege to enjoy. Those prowling fiends who like demons of hell had murdered the innocent and robbed them of their raiment, were still lurking around watching for new victims. Especially all the male members of the neighborhood had to keep concealed. The moment the mob got sight of them, they were shot at. The women were not quite so closely hunted and they, by being extremely cautious, managed to convey water and food to their husbands, sons and brothers, to keep them from famishing. Myself and cousin had to sleep in shocks of corn or in the brush for two or three weeks, not daring to enter the house, and we were kept from starving by the food which our mothers and sisters managed to convey to us. The nights were cold and frosty, which added seriously to our affliction.

After about three weeks from the time of the massacre, the mob sent our people word that we were all to leave that country inside of ten days or we would all be killed. They were doubtless stimulated to make this announcement because of the order of extermination which was issued by Governor Boggs. Whatever the cause was, it was equally cruel to be borne by our people. It affected our family equally with other members of the Church. The burden of all this preparation and removal, on our part, rested first upon my mother. A less healthy and resolute woman could not have had the courage and endurance to grapple successfully with the obstacles that lay in her path. A family of six children upon her hands to be made ready for removal in ten days' time, would have been a wonderful undertaking in a time of peace with an abundance of means at her command. But she had neither peace or available means. True, my father left her 120 acres of excellent land, with a government title, a good crop of corn, already matured and ten or fifteen acres of fall wheat. But all this she had to leave for the enemy to appropriate to their own use. In fact all the comforts of home had to be sacrificed, and with the Saints of God, we had to flee, destitute and hunted, because of our religion.

The names of her children were Rebecca, Nancy, John, Josiah, Austin and Julian. My mother's age at that time was about 32 years.

Well do I remember the sufferings and cruelties of those days. But we knew when the ten days were up that we would have to be on the move or our lives would be sacrificed. The Saints had no opportunity to sell their possessions, except in a few cases, and this is exactly what the mob wanted, knowing that they could take possession after they had compelled our removal.

Our family had one wagon, and one blind horse was all we possessed towards a team, and that one blind horse had to transport our effects to the state of Illinois. We traded our wagon with a brother who had two horses, for a light one horse wagon, thus accommodating both parties. Into this small wagon we placed our clothes, bedding, some corn meal and what scanty provisions we could muster, and started out into the cold and frost to travel on foot, to eat and sleep by the wayside with the canopy of heaven for a covering. But the biting frosts of those nights and the piercing winds were less barbarous and pitiful than the demons in human form before whose fury we fled. The stars looked down upon us from the vaults of heaven, reminding us that God ruled on high and took cognizance of the conditions of those who peopled His earth.

When night approached we would hunt for a log or fallen tree and if lucky enough to find one we would build fires by the sides of it. Those who had blankets or bedding camped down near enough to enjoy the warmth of the fire, which was kept burning through the entire night. Our family, as well as many others, were almost barefooted, and some had to wrap their feet in cloths in order to keep them from freezing and protect them from the sharp points of the frozen ground. This, at best, was very imperfect protection, and often the blood from our feet marked the frozen earth. My mother and sister were the only members of our family who had shoes, and these became worn out and almost useless before we reached the then hospitable shores of Illinois.

All of our family except the two youngest Austin and Julian had to walk every step of the entire distance, as our one horse was not able to haul a greater load; and that was a heavy burden for the poor animal. Everything bulky or anyway heavy was discarded before starting. Such articles as my father's cooperage tools, plows and farming implements we buried in the ground, where they may have remained undiscovered to the present time.

There was scarcely a day while we were on the road that it did not either snow or rain. The nights and mornings were very cold. Considering our unsheltered and exposed condition, it is a marvel with me to this day how we endured such fatigues without being disabled by sickness, if not death. But that merciful Being who "tempers the winds to the shorn lamb," sheltered and gave us courage, otherwise strength and our powers of endurance must have given way and we perished by the roadside. My mother seemed endowed with great fortitude and resolution, and appeared to be inspired to devise ways and plans whereby she could administer comforts to her suffering children and keep them in good spirits. Her faith and confidence had ever been great in the Lord; but now that all this care and responsibility came upon her shoulders, with no husband to lean upon, she felt indeed that God was her greatest and best friend, and she realized that He alone must be the deliverer of herself and family and conduct them to a people possessing the sympathies of humanity.

At last we reached the Mississippi River and were happy indeed. We gazed upon the opposite shore with hearts overflowing with thankfulness to our Heavenly Father, for that indeed was our land of refuge, an asylum, and we hoped there to find a home where mobs would not lay in wait to shed our blood or place the torch to our houses and barns. We crossed the river at Quincy, Illinois, where not only our family but the entire host of exiled Saints found protection and friends whose hearts and hands were open and ready to administer relief.

Our family went to Pike County, where we made the acquaintance of Mr. Hornback. He was kind and furnished us a small house to live in through the remainder of the winter. In the spring, my Uncle William Anderson came and took us to Indiana, to my grandfather Hammer's. After staying in Indiana about three years, my mother was extremely anxious to go to the Church at Nauvoo, and an old friend by the name of Fielding Garr furnished an outfit for our entire family and moved us near to the town of Laharp. All this he did at his own expense, and continued to see that we were provided for until we could provide for ourselves. His two oldest sons Richard and John Garr would haul our wood and chop it up for us.

We remained at Laharp until the Church was again driven; and we with them were compelled to seek an asylum in the wilderness regions of the Rocky Mountains.

My mother's name was Nancy Elston Hammer. She was born in February, 1806, and died at Smithfield, Cache County, Utah, October 10, 1873. She died full in the faith of the gospel and all the doctrines revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith. She rests from her earthly sufferings, which will make her resurrection glorious.

During the last years of her pilgrimage, her mind was much occupied in reviewing her long and useful life. In conversing with her children and friends, she expressed much satisfaction that she had acted her part so well and that the Lord had been merciful in giving her the light of His Holy Spirit, which had been a lamp to her feet to direct her course safely through the darkest perils of life. She has gone to her glorious reward, where the turmoils of the wicked cannot afflict or drive the children of the righteous from the eternal dwellings prepared for them from the foundation of the world.

Yours truly,

John Hammer.”

(Lyman Littlefield, Reminiscences of Latter-Day Saints, Logan, Utah: The Utah Journal Co., 1888, Chapter V, p.66-76.)

Austin Hammer, son of John and Nancy York Hammer was born 6 May 1804 in South Carolina. He married Nancy Elston, 7 September 1826 in Wayne County Kentucky; a daughter of Josiah Elston and Rebecca Lewis. Soon after their marriage they moved to Ohio, where they lived three years. They then moved to Henry County, Indiana. After five years they moved to Shole Creek, Caldwell County, Missouri; where they had title to 180 acres of land.

Austin and sixteen other men were killed 30 October 1838 while guarding Haun's grist mill to keep the mob from burning it. These men were put in a dry well and covered with stray and dirt to cover their bodies. The mob was so bad they did not dare to attempt to give them a proper burial.

After the death of Austin Hammer, his wife took her family of six children and went to Illinois. Their outfit consisted of a blind horse and a light wagon. Their baby, Julia, and the small boy, Austin were the only ones to ride. Little Austin was sick. Only two of the family had shoes. The others tied their feet up in rags and made the journey of two hundred miles in the latter part of November and December of 1838.

Austin embraced the gospel of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and was baptized in 1835, in Henry County, Indiana.